Ebb and flow of the mighty Hawkesbury River

By Ellen Hill Photos: David Hill

(Continuing the story of the Hawkesbury River, we re-publish here an article that featured in the April-May 2009 edition of Blue Mountains Life magazine.)

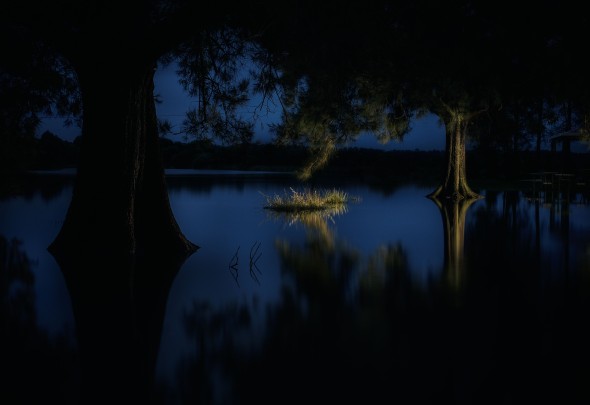

THE last tendrils of fog swirl up to meet the golden rays of a weak winter sun, mirrored on the still surface of the water.

The occasional jumping fish makes a quiet “blip’’ noise. Birds twitter in the trees and skate across the gentle ripples before settling on the surface to float aimlessly with the tide.

This is Ted Books’ favourite time of day to cruise the Windsor section of the Hawkesbury River in his boat, the Montrose. He’s alone.

By mid-morning, the water twinkles in the glaring sun, the river a silver thread pulsing through colonial Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s kingdom with the monotony of routine.

Given the majestic Hawkesbury River has supported his family for five generations, you understand Books’ attachment to it.

As the boat gently bobs along the water, Books’ shares his memories and tells the history of the stretch he knows best _ the strip of water his famous colonial ancestors eventually learned they could not tame.

Ted Books is known for expressing a strong opinion and enjoying a chat. But he’s not known for being an emotional man. A former wrestler and retired excavator, he tends to say his bit in his no-nonsense way and leave it at that.

But aboard the Montrose, I not only see a different side to Books, but the river I have known most of my life.

“Sydney’s salad bowl’’, “Sydney’s playground’’, the Hawkesbury River has supported Australia’s largest city since European settlement.

For the handful of free settlers desperately trying to survive with virtually nothing in a foreign environment, the river was their transport, it watered them, their crops and animals.

In colonial times while chain gangs of convicts were still cutting roads by hand, the Hawkesbury River was the natural highway to Sydney Cove.

In fact, ships including the 101 ton Governor Bligh were actually built on the river. Two of Books’ ancestors _ Captain John Grono and Alexander Books _ had a shipyard at Pitt Town on Canning Reach, the remains of which can still be seen at low tide.

Among the 200 cargo vessel movements on the river each year were tall ships which took three inward tides (about 20 hours) to travel from Brooklyn at the mouth of the river to Windsor.

The 100 ton SS Erringhi was the last of the big ships to trade on the Hawkebsury River between the 1920s and 1937.

“I used to dive off the Windsor bridge and there used to be 30ft of water there,’’ Books says. “We used to dive off the bridge and go with the tide to Pitt Town, about 4 miles by water.’’

The Hawkesbury Nepean River is part of the vast 22,000 sq km Hawkesbury Nepean Catchment, stretching from Goulburn to Lithgow, Moonee Moonee, Pittwater and Singleton.

Its tributaries and creeks begin in the higher land of the Great Dividing Range, others in the highlands to the west of Wollongong and south of Sydney.

The Nepean begins in the Camden Valley near Moss Vale and becomes the Hawkesbury at Yarramundi after being joined by the Wollondilly River, on which Warragamba Dam, Sydney’s main drinking glass, was built in the 1950s.

From the 1870s, a series of dams was built on the Upper Nepean, south east of Camden and its tributaries the Cataract, Cordeaux and Avon Rivers.

The mighty Hawkesbury Nepean River ends at Juno Point at Broken Bay.

“Sydney would never survive without this river,’’ Books says. “This river is the playground for the city.’’

Every now and again Books stops the boat, points out a landmark, pulls out yet another packet of black and white photographs and tells the story of the place.

“See that place up there? That’s where Thomas Arndell (the first surgeon to the colony, he came out with the First Fleet) settled when he came to the Hawkesbury. His homestead’s still there.

“They built next to the river because it was clean water and there was fish.’’

The oldest church building in Australia is at Ebenezer, built from stone in 1803 by a small band of free settlers. The church used to run a punt across the river to transport people to church.

The water is deepest _ about 90ft _ nearby, opposite Tizzana Winery at Sackville Reach Wharf.

Glancing at the river banks from the boat, it seems not much has changed apart from technology. Irrigation pumps spew water across enormous paddocks of turf, veggies and flowers. The staccato bark of a dog sends drifting ducks into a flurry. The sun’s rays highlight the fur on a lowing cow staring with lazy interest at the boat. The ghostly figures of farm workers can be seen inside a row of greenhouses.

But then Books’ tale of how his dad and his mates used to catch more fish than they could eat up this stretch of the river is broken by the roar of a power boat towing a skier.

Books pauses and waits for silence to return before pointing out another historic property on the hill.

He revs up the engine and the Montrose slips on.

The river remains a great source of seafood: flathead, bream, mullet, hairtail, mullaway, whiting, flounder, tailor, snapper, trevally, blackfish, leatherjackets, kingfish, John Dory, shellfish and prawns.

It is also home to much bird life: shags, cormorants, kingfishers, ducks, sea eagles, pelicans and terns.

And down in the salt water near the river mouth at Brooklyn there are sharks, sea snakes, jellyfish, stingrays and fortescues.

Today, the Hawkebsury, Penrith and Baulkham Hills region along the river generates a whopping $1.86 billion worth of produce (not including the equine industry). Sydney chows through 90 per cent of it.

The vast quantities of fruit, vegetables and turf grown in the Hawkesbury have fed the entire Sydney population and beyond for generations.

The river is also a major tourist attraction used extensively for recreation (the annual Bridge to Bridge boat race attracts thousands). Tourism and recreation reap $2 billion a year, thanks to the river.

Three car ferries and several bridges provide crossings over the waterway.

Crowds of day trippers are drawn to popular swimming, fishing, water skiing and boating spots each weekend.

A startling white glare suddenly burns the retinas of our eyes. Deck chairs blindingly white in the sun, emerald green manicured lawns and landscaped yards, expensive boat sheds. The property listings at the local real estate agents would reveal that river frontages are also becoming private paradises for the wealthy.

But later, in the golden after glow of sunset, the birds and fish replay their evening ritual as the mist settles like a gossamer blanket over the water surface, melding with the gloom of dusk. The river continues to beat its slow rhythm of life just as it always has.

Hawkesbury River, NSW: The Settler’s River

The Smith Park picnic area becomes part of Pugh’s Lagoon on the Hawkesbury River floodplain during flood.

By Ellen Hill Photos: David Hill

(As NSW experiences the worst floods in decades, it is worth remembering that flood waters have been a regular feature of the Hawkesbury River for centuries. This feature article by the Deep Hill Media team appeared in the October/November 2010 edition of Blue Mountains Life magazine. It is republished here with fresh images showing the current flood.)

IN 1978, my family moved to Richmond. It was the hottest summer and coldest winter for decades. But it was the rain that sent doubts lapping around my parents’ minds about the wisdom of shifting their young children to what was considered a distant outpost.

That March, the Hawkesbury River rose to 14.31m above Windsor Bridge. Richmond became an island. Our world ended at Chapel St, Agnes Banks and the RAAF base. Cows and farm equipment were brought up to the high paddocks on the fringes of town.

We didn’t know it then, but we and countless others previously and since had one man to thank for our safety – Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

Local Councillor and Hawkesbury Flood Risk Management Committee Chairman Kevin Conolly believes the flame-haired leader would be happy with modern efforts to protect residents against flood – Macquarie’s colonial edicts concerning the floodplain continue to influence town planning in the Hawkesbury today.

But with many newcomers never having experienced a flood, modern authorities face similar challenges to their colonial peers.

Hawkesbury residents have been warned of flood dangers since Captain Arthur Philip saw weeds high in the trees at Agnes Banks. Governor King tried to convince settlers into regions other than the fertile but flood-prone Hawkesbury region.

But on his arrival in the fledgling colony in 1810, it was Governor Macquarie who took firm action and ordered the abandonment of floodplain dwellings.

A March, 30, 1806, report in the Sydney Gazette gives a descriptive account of what Macquarie did not want to see again – “…many individuals lost every thing they possessed, and that several have perished in the deluge, which was never before known to arrive to so great a height by from eight to ten feet. What rendered its progress still more destructive was the false notion of security which many had imbibed, from the supposed confidence that there never would be another heavy flood in the main river…”

Hundreds of terrified souls were plucked from rooftops and rafts of straw but five people died and much of the colony’s food supply was lost.

On December 6, 1810, Macquarie gave his famous after-dinner speech proclaiming the five towns of on high ground above the flood plain – Richmond, Windsor, Pitt Town, Castlereagh and Wilberforce.

Each settler was allotted a plot in the new towns large enough for a house, offices, garden, corn yard and stockyard relative to the size of their flood prone farm.

The swollen Hawkesbury River laps at the deck of Yarramundi Bridge as more heavy rain clouds gather.

But settlers largely ignored him at/to their peril. In 1816 the river rose again to 13.88m at Windsor Bridge, then to 14.03m in February 1817.

Frustration is apparent in Macquarie’s March 5 1817 proclamation when he again ordered settlers to higher ground – “…many of the deplorable Losses which have been sustained within the last few Years, might have been in great Measure averted, had the Settlers paid due Consideration to their own Interests, and to the frequent Admonitions they had received by removing their Residences from within the Flood Marks to the TOWNSHIPS assigned for them on the HIGHLANDS, it must be confessed that the Compassion excited by their Misfortunes is mingled with Sentiments of Astonishment and Surprise that any People could be found so totally insensitive to their true interests, as the Settlers have in this Instance proved themselves.”

A new benchmark was set for town planners in June 1867 when the Hawkesbury River spilled 19.26m above Windsor Bridge.

Fifteen members of the Eather family were swept into the swirling torrent at Cornwallis on the night of June 21. Twelve drowned, including Catharine (just 36), Emma (38), and five children apiece. Ironically, Catharine is buried opposite the start of the new flood evacuation bypass in Windsor.

Modern scientific evidence suggests an even greater inundation is possible, one where all that can be done is evacuate as many people as early as possible. Referred to as the probable maximum flood (PMF), experts predict it could reach 26.4m above Windsor Bridge.

Hawkesbury Council has successfully lobbied governments for flood evacuation routes – Richmond and Londonderry roads have been raised, and a new bypass built between Windsor and McGraths Hill. A higher Windsor Bridge will be built soon, and council continues work with the State Emergency Service (SES) to fine tune evacuation plans and procedures.

Lobbyists like Clr Conolly and former farmer John Miller continue to demand that more be done, including raising the Warragamba Dam wall by 4m, which would lower floodwaters by the equivalent of two house storeys, they say.

John Miller, 81, knows firsthand about floods in the Hawkesbury. Heady with romantic ideals of farm life, he brought his pregnant wife and toddler to his new farm at Sackville in 1955. In 1956, seven floods wiped out every fruit and vegetable crop he planted.

“I knew nothing about the 1867 flood or any other flood. I’d never a seen a flood before … I got to the bottom of the farm and there’s water up to my packing sheds, and I was carrying bags of fertiliser on my back because it had been raining for weeks, and I kept sinking down in the mud. I didn’t know until I bought the place it was called Mud Island.”

After asking neighbours about his property, John relates “he said ‘Well, in 1867 there was a two storey house there and it was washed away, and a bloke found it at the bottom of the Ebenezer gorge’.

“I couldn’t make a go of it so I moved out of the area and grew mushrooms.”

The zone around John Miller’s former farm is where floodwaters are deepest and most furious. When the Hawkesbury Nepean River floods the water doesn’t just gradually rise – Mother Nature throws a tantrum.

It only takes a few days of very heavy constant rain to cause severe flooding in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley because water surges into the valley at a much higher rate than it can flow out. When the water hits the narrow sandstone cliffs at Ebenezer/Sackville, a bottleneck causes the water to back up into the Richmond/Windsor floodplain before heading back down for another go at squeezing through the cliffs.

Meanwhile, anything in its path is ripped away and catapulted downstream at great speed. “You’ve got tree trunks” John Miller says. “You’d see them go under the bridge and then spear out of the water as they came out the other side. It was horrifying.

“Some people say to me ‘We’ll never get another flood again’ and I say ‘No, and we’ll never get another bushfire in the Blue Mountains either, will we?’ Some people have said I’m a scaremonger, but I’d hate to have to say: `I told you so’.”

Clr Conolly agrees – “The risk is certainly very real. There will be another flood, but there are a lot of people who are not familiar with the fact that it does flood, and the magnitude of floods in the Hawkesbury.

“Macquarie took a very sensible approach and saved many people’s lives. We’re trying to do the same.”

Living high and dry above the floodplain these days, I can only hope others will heed the warnings too. *

FLOOD FACTS

• Captain Arthur Philip sees weeds in the trees when he camped on Richmond Hill at Agnes Banks while touring the Hawkesbury Nepean River in 1789

• Governor Philip Gidley King tries to persuade settlers to “set a greater value on the forrest lands’’ of Toongabbie, Parramatta, Prospect Hill, Castle Hill, Seven Hills and Port Jackson after the devastating October 1806 flood when the river rose 14.64m above Windsor Bridge

• May and August 1809: floodwaters rise 14.64m and 14.49m above the bridge respectively, devastating the colony’s food supply

• December 6, 1810: Governor Lachlan Macquarie names his five towns and orders settlers to abandon their riverbank homes

• March 1817: Macquarie strengthens his order to abandon the floodplain

• June 1867: 12 members of the Eather family drown when floodwaters rise 19.26m

• 1960 Warragamba Dam completed

• November 1961: the river rises 15.1m

• March and June 1978: floodwaters rise 14.31m and 9.55m respectively

• February 1992: the last Hawkesbury River flood when water rises 11m above the bridge

• June 2002: $150 million Warragamba Dam auxiliary spillway completed

FLOOD STORIES

• On the right hand side of Cornwallis Rd about 1km from the Greenway Cres and Moses St, Cornwallis, intersection is a simple sign commemorating the tragic demise of 12 members of the Eather family swept into the torrent on the night of June 21.

• One of the 12, Catharine, is buried in Windsor Catholic Cemetery, Hawkesbury Valley Way and George St, ironically opposite the start of the new flood evacuation bypass in Windsor.

• The height of the 1867 flood is marked on the side wall of the Macquarie Arms Hotel at Thompson’s Square, Windsor

• Away from Windsor, markers can be seen throughout the Hawkesbury to commemorate floodwater height and the location of significant sites including behind St James’ Anglican Church, Pitt Town; and the location of the original church at Sackville Reach near the cemetery on Tizzana Rd.